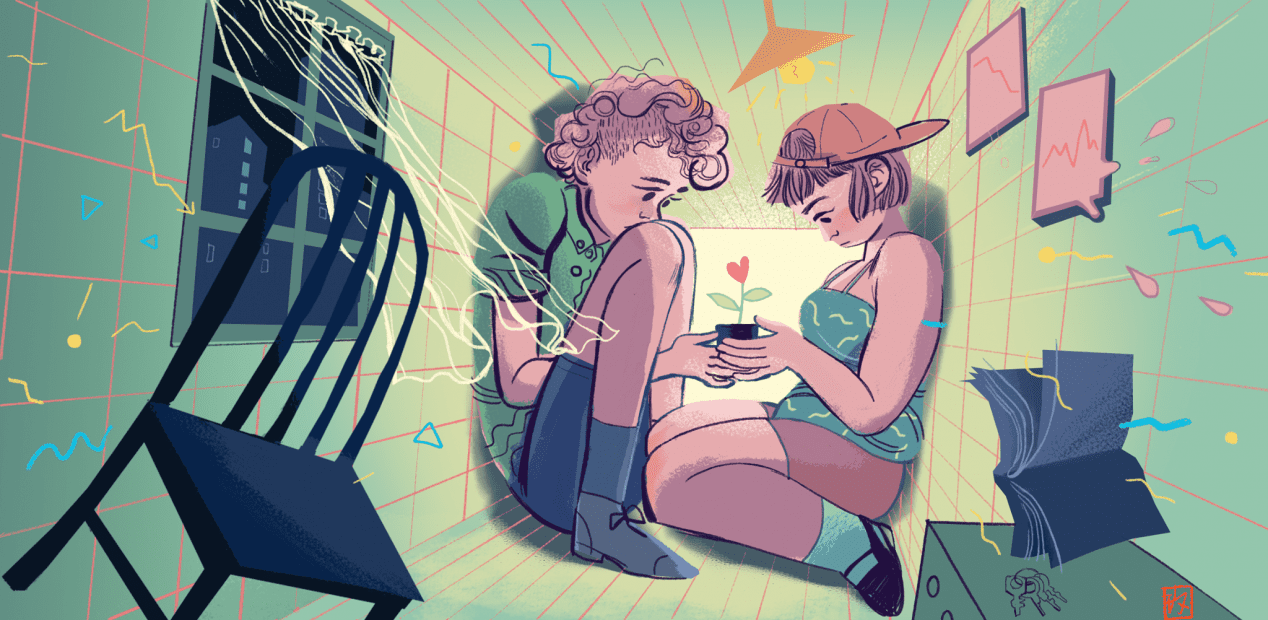

It wasn’t exactly the show of commitment 28-year-old Kelly grew up expecting to receive from her some-day life partner. As a child in the 80s and 90s, Kelly was surrounded by the influence of wedding pop-culture, and like many little girls, it left a mark.

“Everything around me as a child was how you prepare to get married, like picking wedding dresses and all those girlie things,” she says.

Yet when Julien, her 33-year-old partner of over five years made a proposal that would legally entwine their futures, it didn’t come in the form of a ring. Rather, he named her as the sole beneficiary of his life insurance policy.

“I thought about it and realized that’s like a sign of commitment,” Kelly, a childcare worker, says. More than that, though, it’s a sign of the times.

Shedding wedding culture

It’s no secret that young people are putting off marriage, or foregoing it altogether. Across the country marriage rates have been declining steadily for more than 30 years while the age of first marriage has been increasing steadily. According to the National Household Survey, 73 per cent of 25-29 year-olds had never been married in 2011, compared with just 26 per cent in 1981. The rate of people in their early 30s who had never been married also jumped considerably during that time, with 54 per cent of men and 43 per cent of women having never tied the knot in 2011 (up from just 15 per cent and 10 per cent respectively 30 years earlier). Meanwhile the age of first marriage in Canada now hovers around 30 for men and women, compared to 23 for women and 25 for men in the 1970s.

The reasons for this are manifold. Social mores no longer require couples to get hitched in order to legitimize coupledom, cohabitation or child rearing—a factor that Julien admits has him putting marriage on the back burner. “I think if we were in a world where someone else could be proposing to Kelly and I had to secure the relationship I’d be under more pressure to propose and secure the deal,” says Julien. “But that’s not really needed in today’s society.”

Common law couples

Indeed, it is not. Under B.C. law, couples that cohabitate for two years or more are effectively legally married and entitled a 50/50 split of property, debts and assets acquired during the relationship. These couples can even go after divorce-like settlements if the relationship ends. But while common-law couples are as good as married in the eyes of the law, from a personal standpoint walking down the aisle still seems like a bigger, much more daunting, commitment. And for millennials who grew up in an era where divorce and separation became commonplace, marriage often feels like a risky step — and an expensive one at that.

Would you spend $30,000 on a party?

According to WeddingBells.ca, the average wedding in Canada costs between $20,000 and $30,000. For young couples grappling with the cost of living in Vancouver, that kind of money is hard to come by. And if you have it, a wedding doesn’t necessarily seem like the best use for this money to many.

But the mingling of finances also serves another purpose in modern courtship. With couples taking a long time to decide whether to make a formal long-term commitment, each financial milestone also provides a mechanism to evaluate whether the relationship should continue.

“The financial steps kind of come along with the emotional commitment,” says Kelle, 34 a kayak guide based in Squamish. “They kind of go hand-in-hand.”

Another kind of milestone

After nearly a year of “going steady” with her boyfriend Sean, 35, the pair recently reached one of those milestones while sharing expenses on a vacation. “We were on a road trip with my family in the Okanagan and we were sharing a lot of costs, taking turns for paying everything. I thought if we opened a joint chequing account and each put money in it, then we know that it’s split exactly 50/50,” Kelle says. The move was purely motivated by pragmatism, but she admits it also came with some emotional heft. “It sounds really scary, it sounds like it’s a way to anchor someone into a relationship a little bit,” says Kelle. “I’d never asked anyone to do that before.”

Fortunately, Sean didn’t feel that way. He agreed that kind of commitment came at an important time in the couple’s relationship. “You’re going to all these dinners and parties together and all this stuff and you’re like ‘wait, I’m really dedicating here,’ it makes you stop and think ‘is this a good idea?’” he says.

Putting the option of combining finances on the table has provided an important opportunity to take stock of each partner’s investment in the relationship, both emotional and financial. And the pair has already toyed with the idea of making some bigger purchases down the road, says Sean, noting that doubling your purchasing power is a powerful motivator for young couples in Vancouver.

Finance is romance

Even among millennials for whom marriage is a priority, tying the knot is often financially motivated, adds Patrick, a 26-year-old student who is engaged to his partner of three years. Although already common-law with his partner of three years, the pair is getting married next summer in a move that was equally inspired by personal and financial aims. “For the most part marriage is a legal document,” says Patrick. “Getting married will make us owning a place simpler and our taxes become easier. It’ll be easier to look after our money that way and to leverage credit for things. I guess I’m not going to come off as a romantic in this article.”

While millennials might have a reputation as an impulsive generation motivated by short-term goals like exciting trips, glamorous careers, and the reluctance to jump into long-term commitments—many are far more concerned with security than the stereotypes, or their carefully crafted online images let on, says Patrick. With less financial and social mobility than the generations before them, formalizing some sort of commitment to support your partner now and in the future becomes important. “It gives you a sense of security,” he says.

Whether that comes with a wedding or not is sort of secondary. For her part, Kelly says she’s come to see Julien’s commitment as a romantic gesture — even if it’s not quite emblematic of the storybook narratives she was exposed to as a child. “It was a physical commitment, it’s not necessarily massively financial, but it showed my importance to Julien. That’s how it felt to me, anyway.”

But she hasn’t totally let go of the desire to get married. “I think for me it’s more about the public commitment from one person to another, not necessarily being married in the eyes of the law,” she says. “It would also be nice to get kitchen ware.”

This is the second part of a two-part series on how affordability challenges affect dating and commitment for young people living in Canada’s most expensive city. Read part 1 here.